The Most Hated Man in the Southern States

Chapter 18

The dawn of the new year of 1864 brought little rejoicing in the Confederate States. There were men who were glad to see Jefferson Davis pass, as horrible as it may sound for one man to rejoice in the death of one who should have been an ally. They were Senators and Representatives, Governors and - shamefully - Generals of the Confederate Armies, all of whom had been thwarted in some way by President Davis. One of the men who rejoiced in his heart, for all that pious platitudes poured from his lying lips, was now President in Davis' place.

Our situation was bleak. Tax revenues to the government were non-existant; the export of cotton, which provided so much of the pre-War revenue, had slowed to a trickle. Once we scoffed at the paper blockade, now we strained to count the host of Federal vessels that circled outside our ports. Wealthy men were destitute, planters ruined, banks closed, mercantiles reduced to the display of empty shelves. The great plantations were given over to raising root crops, or a patch of grain, or a few scraggly cows. Such food as could be had was taken with promissory notes - worthless paper trash - for the armies; little enough remained to feed the women, children, aged, infirm and the slaves who remained on the farms. The Confederacy endured, but we knew how brittle and feeble our nation had become.

Many slaves did not remain, and there were no men to be spared from combat to go after them. Lincoln's proclamations and Federal laws had no force in the South, but they drew slaves North to freedom as a magnet pulls iron filings. Where the runaways were caught, the trees grew strange and fearsome fruit indeed, but hundreds won through for every one hanged, and every slave that left the South depleted our labor force at a time when labor was more precious than gold.

On every street were the wounded; armless, legless, blind, scarred with ghastly burns, penniless and pitiful in their wretched destitution. Major buildings in every city were converted to hospitals for the wounded, and the chorus of misery that arose from them silenced every sound it seemed but the funereal, constant church bells tolling for the dead. Every home had a window adorned in the bright, mocking color of a crimson star denoting a loved one lost in the country's service. Or two. Or more.

Of the currency I can only say that the death of Davis, and the continuation of a ruinous War with no end in sight, had so depleted the public confidence that Confederate national notes were treated at their true value - as waste paper - and the bank notes of the various states were even more despised. Inflation of prices was a daily occurrence; a man who had money and did not spend it instantly was a fool, for it would be worth even less on the morrow. Food riots began to occur in our cities - riots! - as our suffering citizens begged for bread from government warehouses. Davis might have spoken with them, or even distributed some food; Rhett, in the first real act of his Presidency, ordered up a militia and bade them fire on the hapless mob! Cooler heads among the militia officers prevailed and the ladies were induced to disperse, but the hard feelings towards Rhett would never fade. In that throng had been the wives, daughters and sisters of the bluest of Virginia blood, and from that day on, the Rhetts were not received in society.

One enduring memory of this time is of the funeral services for Jefferson Davis, the formal services in Richmond, and the gathering after where there was no refreshment in the fine silver and crystal punch-bowls but iced water. At first I believed this was in token of his memory and in the spirit of his calls for sacrifice, but in truth it was because there was nothing else to serve. I rode in the funeral train that carried him home to Mississippi for burial near the burned-out ruins of his former home. I remember the grieving thousands who lined the tracks, lifting squares of black cloth in tribute to the departed hero. If truth must be told, Davis was beloved more in death than he had been in life.

Despite these crises and others, the trains continued to run and the armies continued to fight. Of the heroism of my train crews and track gangs my tongue is inadequate to speak. Many of them by this time were wounded soldiers or former slaves, and as they performed the labors of Hercules with loyalty beyond reproach, so I endeavored to improve their lot whenever possible. Slaves were bought and worked as freed men, foodstuffs and blankets procured and distributed, families of dead and wounded railroad men looked after. I could do little - pitifully little - but in honor I could do no less.

Grant's failure at Shiloh in 1862 had been balanced, in part, by Rosecrans' success in the East. Moving rapidly into Virginia he succeeded in pinning a portion of Lee's army on the old battleground of Chancellorsville, where Lee delivered a flank attack from Longstreet's corps before deciding it was best to retreat to a better position. As victories go it was not much, but it did offer Lincoln a chance to unveil his proposal for ending slavery: the Transportation Acts.

I have heard since the War that Lincoln desired to issue a proclamation of emancipation for all slaves, but was dissuaded by members of his cabinet. These Transportation Acts fell short of emancipation, but they did address five points. Firstly, the Fugitive Slave laws were repealed. A slave who crossed into free territory was, from that moment and forever, free. Secondly, the armed forces were entitled to seize Confederate property - including slaves - as contraband, use the seized property to assist the War effort without compensation to the owners, and offer slaves their freedom at the end of a fixed period of service. Controversially, public land was to be set aside in the Arizona and Colorado territories for any male slave born before 1844. Any child born to a slave after January 1st of 1863 would be a free citizen. And finally, any person owning slaves could sell them to the federal government for a fixed amount of public land; the government would then free them and award them land in the territories.

It was an inelegant and cumbersome system, allowing for the gradual phasing out of slavery rather than its immediate end, and it met with a mixed reception in the North. Some complained it did not go far or fast enough; others that it went too far and too fast, and cost too much to boot! But it was a body blow to the South; at one stroke it rendered aid from England or France inconceivable, and as I have said the flow of runaway slaves became a torrent.

In this year of 1864, Rosecrans was slowly forcing Lee back on Richmond. Vainly did Lee plead for Beauregard's troops to be sent to Virginia for an offensive northward; Rhett had never cared much for Lee and was not now disposed to send him more than the minimum required to secure Richmond. Beauregard's 'Railroad Corps' was to be used instead to break the Federal hold on the North Carolina sounds and the South Carolina coast at Port Royal. Such a plan might well have yielded some badly-needed victories for few casualties, or even disrupted the coal supply for the blockading ships and temporarily raised the onerous blockade of Charleston and Savannah. But the North, with its superiority in men and supplies, was to dictate the events of 1864 instead.

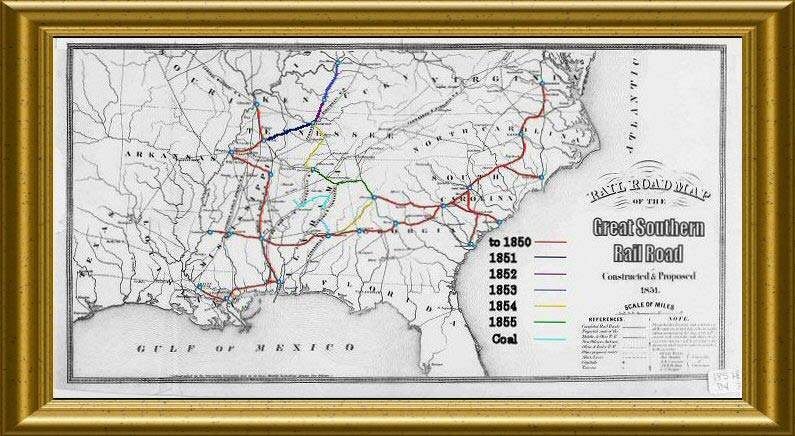

While Rosecrans kept up pressure in the East, Sherman assembled a vast army in Lexington, Kentucky, more than 100,000 men by the end of 1863. Superbly equipped and supplied, these men were to spearhead a stroke that would split the South in half at its most vulnerable railroad juncture: Atlanta, Georgia. Moving south from Lexington and laying temporary rail as needed, Sherman's corps could punch to Knoxville, liberating an area that was solidly pro-Union. Westward forays would disrupt our railroads from Louisville to Nashville and might induce the Confederacy to give up those cities. But in any event Sherman intended to press down the railroad from Knoxville to Chattanooga, and then on to Atlanta.

The Huntsville-to-Atlanta-to-Augusta-to-Charleston road was not the only railroad line across the Confederacy, but it was well graded and maintained, able to handle a high volume of traffic and high speeds. Breaking this line would seriously impair our ability to support the armies in Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi. A Federal force securely established in Atlanta could easily turn west, east or south - and kick the heart out of the Confederacy. Our gunpowder mill, arsenal and the iron smelters and foundries would all be within easy reach of an enemy in Atlanta.

In the face of this danger, we worked around the clock to reinforce General Braxton Bragg's Army of Kentucky, currently encamped at Perryville. (General AP Hill, its former commander, had been tendered command of the Mississippi Valley and western regions and Bragg now commanded the new Central Department). Bragg refused to abandon the smoldering rubble-heap of Louisville, which drew off troops from his army but also forced the Federals to maintain garrisons on the north bank of the Ohio River. In any event, Sherman surprised everyone by launching his movement over hard-frozen roads on New Year's Day. He certainly surprised Bragg by driving past the latter's right flank and apparently exposing his own left, at which Bragg promptly struck. As successful as it was, the stroke did not completely penetrate the Union line, and Sherman's counterstroke broke up Bragg's corps and threw the army west in disarray. Bragg withdrew to Elizabethtown, then south down the railroad toward Nashville as Sherman marched south on Knoxville, leaving a token force to control eastern Kentucky.

The usual expedient of raiding Union supply lines with Confederate cavalry was tried and largely failed. Herman Haupt and others of the US Railroad Service kept the track open despite the raids; men began to say it was no use dynamiting tunnels and burning bridges because Sherman kept spares in his coat pockets. Sherman was not depending on the railroad for very much beyond ammunition and a little coffee, in any event. And Federal cavalry had improved; Sheridan was surprised by Nathan Bedford Forrest at Somerset, and beaten in a two-hour running battle in the morning, which was not in itself unusual for Forrest to do. What did surprise us was that Sheridan gathered up the elements of his command, struck across country and smashed into Bedford Forrest's column in the afternoon, handing Forrest a rare - and very costly - defeat.

By the end of April, Bragg had gathered his forces in Nashville and Sherman had occupied Knoxville. When President Rhett read in the newspapers that Bragg was preparing to burn Nashville and retreat further south, he took a special train west and sacked the General on the spot. By Presidential telegram, Beauregard was commanded to take up the central department and bring his 'Railroad Corps' along as reinforcements. There was not a moment to be lost; Sherman had unleashed Sheridan's corps east from Knoxville into the Shenandoah Valley and was himself driving south-west on Chattanooga.

The Great Southern had never run lines to Chattanooga. It was a pretty enough little town on the south bank of the Tennessee River, too far upstream from the shoals for riverboats to navigate, in the heart of some rough hills and difficult terrain. Our lines had gone farther west from Atlanta instead, through Huntsville, Alabama to Memphis and Nashville in Tennessee. A group of Atlanta businessmen had, however, bought up the old charter of the Western and Atlantic and had driven lines from Atlanta through Chattanooga to Knoxville, and from Richmond west through Roanoke, Virginia down a great valley in eastern Tennessee to link up with Knoxville from the east. They had done well enough by their investment; had War not intervened I would have considered buying up that line.

As it was, we struggled to shift Bragg's old army from Nashville to Atlanta to Chattanooga while at the same time moving Beauregard's troops from the Carolinas coast to the same city, the road bed and equipment of the W&A being not of the standards of the Great Southern. It was a race between our troops and those of Sherman, a race we both won and lost, for Sterling Price's corps occupied the city only to be thrown out a week later. Beauregard staged a miracle of improvisation, literally unloading trains on the outskirts of the battlefield, and was able to bring up enough men to bloody Sherman's nose as he tried to come through the gaps in Missionary Ridge. Still, it was no great victory and no-one believed Sherman was stopped for long.

We met in Atlanta in June, General Beauregard having taken a few days away from the army and President Rhett having come down from Richmond by special train in a private car. The meeting was brief and notably unpleasant; I had thought the President would wish to review the army and perhaps speak some appropriate words, but Rhett insisted he had no time to spare. To the General, the President was cool and abrupt: the enemy must be thrown back from Southern soil, and if the General was not up to the task, he should say so. Beauregard was icily polite in return, insisting only that he needed a bare sufficiency in numbers of troops, which he did not now possess. In turn, I replied that we were stretched to the limit with troop movements and supply requirements, but that another ten or twenty thousand troops could perhaps be transported if they could be found. Rhett immediately authorized Beauregard to draw upon the garrisons of Charleston, Savannah and Mobile for the requisite number, remarking in parting that the General must bear the blame if any harm were to come to those places as a result.

With Chattanooga lost, Atlanta at risk and the outcome of the War itself in doubt, we came now to the railroad's greatest challenge.

Summer in Georgia is always hot and almost always dry, but the summer of 1864 was exceptional even in the memories of the most aged. Crops withered in fields of sun-baked dirt, so thin and dry it sifted through your hands like flour and spun up into whirlwinds at the least touch of a breeze. Trees were stooped and brown with drought, green leaves hidden under a thick coat of red-brown dust. Rivers vanished, exposing their cracked beds to pitiless daylight, and day after day the sky was bereft of clouds and the sun beat down in wrath.The only wet spots in Georgia, the soldiers said, were underneath the dead and wounded.

There was no escaping the War that summer. The fortunate few who were outside the sound of the guns were exposed daily to want and privation, to the sight of the wounded, assaulted by the incessant funerals. From Texas all the way around to old Virginia, the South was ringed in fire, but no-where in that fiery furnace was the War more intense than in Georgia. Lincoln had found his men, and the Northern people had, at last, put in their full effort, and bit by bit the Confederacy was dying. Newspapers and the telegraph brought news of defeat daily, and if there were no great disasters, there were no offsetting successes. The coast of Texas was lost, Charleston besieged, Lee's army driven around Richmond in a great arc, holding tenuously to the capital while striving to keep Petersburg and the vital railroads open. Daily, more of Georgia was covered in Federal blue as Sherman drove his men relentlessly forward, until at last Atlanta itself was fortified and bombarded.

At night the ring of campfires of the two armies could be traced, a flaming circle halfway around the horizon with dark and silent Atlanta at its heart.

In this extremity, I was called to the headquarters of the Army of Tennessee for a meeting with General Beauregard and his staff. I had no good news to impart and indeed much of the other sort; despite our best efforts, the Great Southern was collapsing. As a horse may stagger on in the traces, lathered and heaving in fatigue, so the poor railroad groaned on, each additional day of service a miracle. But as that horse will fall to the ground never to rise again, we were approaching a point at which the railroad could support neither the armies, nor the populace, nor itself. Our skilled workmen were long since gone into the armed forces, many of them now dead or wounded past ability to work. Without skilled men, we could not repair the worn out and damaged equipment, or make more. Without raw materials - there were no miners to be had - the factories were almost still. As the rails wore out and the engines broke down, we drove the remaining engines and cars still harder, foregoing maintenance and repairs with grim and inevitable results.

"General, we are scarcely able to provision the armies, much less build up any reserve store. The people of the countryside are destitute, and - I say in confidence - the people of the cities are nigh to starve. The government does not wish it to be known how deep is the privation, lest the morale of the armies should suffer." Around the parlor, heads were nodding; these men had letters from loved ones and family and they had heard the doleful tidings despite the government's attempts at secrecy. "I will do anything in my power to assist you. I fear, however, that may be less than either of us would desire."

Beauregard looked around the room, eyes resting on each face in turn, and what he saw there seemed to give him renewed resolve. "We - myself and my staff, with the approval of the President - have prepared a little surprise for General Sherman. General John Bell Hood has assembled an army corps from Texas, Louisiana and western Tennessee. We have stripped the garrisons to the bare bones and all but abandoned the campaign in Arkansas, but General Hood now has more than twenty thousand men at Memphis. We have put out that he intends to strike north, to St Louis or Cairo, but in fact we intend to entrain his troops, transport them east and strike Sherman on his flank." I made to speak, but he continued remorselessly. "To this end we will require additional ammunition stocks and sufficient rations and equipment. My staff have prepared lists." A Colonel whose name I did not know passed over a sheaf of papers covered in a fine copperplate hand. As I could not trust myself to speak, I lowered my brimming eyes and riffled through the lists until I came to what I had feared I would see.

"I believe we can muster the trains to move General Hood's corps, but I will do so only on signed authorization from the President. The diversion of so many engines and cars will leave none for civilian use; no passenger trains, no transportation of sundries or even groceries. The people of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee will be thrown back entirely on their own resources, and I want everyone to understand this before I agree. Every day the trains and cars are employed in service to the armies, the more likely it becomes that disaster - famine - will scourge the western states this fall and winter. The death toll, General, will be frightful." As much as my plain speech distressed the assembled officers, I knew I must continue. "These ammunition stocks cannot be conjured from thin air. This quantity represents the very last of the reserve my company has hoarded since before the War. General Lee will have no powder for the offensive stroke he has planned, and - General Beauregard, I must speak plainly - if this gunpowder is expended, you will find yourself sorely lacking in the fall."

I had not remarked how much Beauregard had aged since the War began, but he turned his head and closed his eyes briefly as if in pain and the light shone full upon the severe new creases in his face and on the strands of gray in once-black hair. At last he opened his eyes and turned back to me, lips lifting in a rueful smile. "Mister Haynes, if we do not hold Atlanta - if we do not throw Sherman back, and soon - the South will be nearly cloven in twain, neither half much able to succor the other. If Atlanta falls, the people of the North will take a new heart, and drive onward with confidence. If Sherman wins a victory here, Lincoln may win re-election in the fall, and while Lincoln speaks for the Union there will be no peace."

"We have come to our Rubicon, as poor a substitute as Peachtree Creek may be, and I think we must cross regardless of the cost. I will ask the President to send you the authorization you seek. And I beg you, sir - I earnestly beg of you - do your utmost. We must have those men, as quickly as possible. I will risk battle regardless, but I cannot be confident of success unless supported by General Hood."

With such a crisis looming, you may think it odd, or selfish, that I should immediately take my personal train to Mobile, but there were good reasons for the journey. From that city I would have easy contact with the remaining senior officers of the Great Southern, and ready access to our machine shops. What we would need was a surge of effort to put the maximum amount of rolling stock in use even if it could only be maintained for a short period of time. Too, there was the necessary scheduling of hundreds of cars of troops, and the almost-insuperable obstacle of procuring enough crew. Then, too, there was a pressing personal need; in this last year my wife's health had steadily declined. The reports from her family had grown so dire that I could do no less than go to her.

Despite what I had heard, I was shocked - appalled! - to see my darling Caroline so wan and frail. Since the death of our son her sadness had almost overwhelmed her, and where I had the anodyne of work to occupy my mind, she had suffered the torments only a bereaved mother can know. Our visit was brief, but it seemed a tonic to her, and in truth I confess I found my own spirits much revived by her sweet love.

To my surprise, crewing the trains proved the least of our worries. As appeals for assistance went out, posters went up and newspaper advertisements were published, the people of the South volunteered in droves. Former slaves, wounded soldiers, old men, boys - even women! - filled out our crew lists and manned our labor gangs. Leaving the work of scheduling the troop movement in the hands of experienced dispatchers, I went on to the powder mills. The thick-walled store-rooms were carefully emptied out by laborers in felt slippers; cartridges, shells, fuses and barrels of gunpowder in various grades were loaded into boxcars specially prepared to limit the risk of sparks or flame.

I remember that the last train had departed for Atlanta when the telegraph came from Richmond; I gave it no more than a cursory look to confirm it authorized the troop movement before stuffing it in my pocket. As he did every night, the chief clerk aboard my rolling headquarters went through my pockets and sorted out the correspondence, filing it away for future need. Had I spent more time studying that telegraph...

No. I would have done as Beauregard asked unless the President had forbidden it outright, and Rhett was too canny for that. Still, I may in fairness say that a close reading of that telegraph might have saved me much misery later.

The movement of such quantities of rolling stock could not be hidden; there were Union spies in the South as there were Confederate sympathizers in the North. We told our men (and women!) the trains were to support Hood's march north. Later, we let out that Hood's corps would be railed to Louisville for a strike into Ohio. But finally, the engines and cars arrived, the coal stocks were laid in at waystations, the sidings were cleared and the switches were staffed, the troops shuffled aboard in the dead of night and the trains pulled out without so much as a whistle. I moved my rolling office on ahead in readiness, to a siding east of Decatur, Alabama, and at the designated hour the trains began to roll.

I fell asleep that evening over my desk, deaf to the chattering of the telegraph key and the scratching of the pens of the clerks. When old Dobbins, my chief clerk, awakened me I thought he was only trying to send me off to bed, and for once I was more than willing to go. At first his urgent message did not penetrate my sleep-addled mind, but on the second or third repetition I thought I had grasped the sense of it.

"Raiders! Is the track safe?"

"Yes, sir - for the moment. Yankees dressed as civilians seized a work train west of Huntsville and tried to burn a bridge. The work gang fought them off, but the Yankees cut the telegraph and got away on the engine."

"Cut the telegraph... yes, that makes sense. I suppose once they got away they stopped and cut it again." Then realization struck. "Dobbins, if the telegraph is down, however did we get the message?"

"The dispatcher shut down all traffic and passed messages in relays down to Montgomery and up through Atlanta, sir. We're receiving from the other side."

"Good man! And where is this runaway train now?"

"If they don't stop, sir, they should be passing us in half an hour."

"We've no troops... Wake the train crew, Dobbins. Tell them to get steam up and tell the clerks to secure for movement. Then open the gun cabinet."

"What are you going to do, sir?"

"I have an army to deliver, Dobbins. And no-one is going to stop me."

One of my clerks - Martin, I think was his name - was invalided out of the army, having lost a leg in Virginia. He took charge of our meager arsenal while I went forward to speak to the locomotive crew. I thought it imprudent to pull my little train off the siding and attempt to block their way, as we had few enough men for a gun battle. If we could get on the mainline ahead of them, however, we could certainly hold them to a slower pace and gain time for troops to assemble.

The engineer was a man near my own age, MacLeod by name, a railroader from the first days and a veteran of the Mexican War. He was not optimistic. "We banked the fires," he said. "Thot we'd be on this sidin' two-three days." I was not interested in placing blame, nor in excuses. "I don't care what corners you have to cut. I want steam up immediately, enough to get us on the mainline and headed east." He shook his head. "Barlow's a fine enjin' but he needs a good head a steam. Have it in an hour, no faster."

No argument would move him, and in truth I suspected he had the right of it. For my personal train I had the use of the Governor Barlow, one of a handful of fast express engines we had begun producing before the war. That class had gigantic driver wheels and could attain amazing speeds while pulling light passenger and mail cars, but they sacrificed pulling power and did indeed require nearly full steam to move at all. I told him he had best make steam faster than ever he had before, and went back to my private cars to see if I could be of assistance there.

The clerks and crew were laying on the track under the cars for protection, spaced well apart and armed with pistols and the carbines from our little armory. I sent Dobbins to turn out the lamps in the cars and took a carbine myself. Martin told everyone to shoot at the engine and engine crew but only if I fired the first shot, and then I settled myself beneath the rearmost car.

I had no time to make myself comfortable before I heard the distinctive huffing of an older American type. Most of the early members of that class were now employed as switchers or as motive power for work trains, but there was always a chance this locomotive was not the one hijacked by the Yankee raiders. It did not slow as it approached the switch for the siding, which we had been too distracted to think of throwing, but came on at what was probably its best speed.

As it came alongside the siding, I could see the laboring engine, the tender and only one flat-car car in the rear. This had to be our stolen train! Taking aim as carefully as I could - firing up at a sharp angle from a prone position in the dark is far from easy - I fired. None of us could see much more than the black bulk of the locomotive, and so quickly did the enemy pass us I do not think even the revolvers got off more than a couple of shots. They were not caught by surprise, but they had not expected us to be on the ground, so all the return fire went over our heads. One shot broke an oil lamp at a clerk's desk; we might have lost the entire train had we not turned them out.

Once they were past, I went up the line. None of our men was injured, nor had our tender or engine sustained any damage we could find in the light of our handheld lamps. The engine crewmen were frightened and angry but unhurt; so furious was the engineer that he was helping to shovel coal and oily waste rags into the firebox, the only time in my life I ever saw an engineer do that! By the time we had steam enough another half-hour had passed, but as yet we had seen no sign of pursuit of the raiders, so I knew we must go on. Before the telegraph tap-line was taken down and stored aboard, Dobbins brought me one last update: troops were assembled a few miles west of Atlanta, but could not be brought farther as there were no ready engines or cars. The track itself was taken up with a freight headed west to Huntsville, a heavy freight of cars filled with coal and pig iron.

There was nothing for it but to do the best we could do, and so I stationed the men with carbines - myself, and Martin - in the cab of the Governor Barlow, and we set off.

No sooner had we rolled past the switch and picked up the man who reset it than the engineer began manipulating the throttle and the injection valve. "We'hs heavy 'caws we'hs full up on wawtah, and Singleton Hill is right ahead." He motioned at my carbine and said, "You best be ready, suh. We be on 'em at Somers." I had no idea what he meant, but instead of yielding to my frantic anger I asked him politely and so he explained; he had seen the engine and tender as they went by. "Those work trains git th' old tenders, suh, an' they don't hold much wawtah aytall." If he was right then our enemy would indeed need water, and the nearest water-tower on this road was at Somers' store, about a half-hour ahead once we got up to speed. Climbing the grade over Singleton Hill slowed us still more, but the engineer used the slight downgrade on the other side to roll us up to forty miles per hour or better, and as the moon had now risen we had light to see what lay ahead.

The approach to Somers was a straightaway of several miles and fields lay on either hand the entire distance so there was no hope we could come on the raiders unawares. If they were indeed at the water-tank at all, they would be prepared for our arrival, and we had no knowledge of how many they might be. I asked the engineer to make the best speed he could given that we might have to stop or even reverse suddenly - I could not throw my handful of untrained men into a firefight at night with men from the Union army.

Our enemies were indeed attempting to water their purloined steed. In the moonlight we could see men swarming around the train, and a few dropped to the ground to open fire. We had no ammunition to waste and so did not return fire, and indeed save for one bullet we heard graze off the body of the Governor Barlow the enemy's shots went wide of the mark. My greatest fear was that the raiders had uncoupled the flatcar to block the track, intending to swarm over our train and seize it as well. Whatever their plan may have been, the stolen train did pull out with the flatcar in tow, and the men who had been firing at us went scrambling to get onboard. Martin and I opened fire then, and the men who had been leaping for the flatcar went down in the dirt for cover.

I told MacLeod the engineer to reduce speed a little. "If we go too fast we'll ram them, and we might knock ourselves off the track." "Too slow and those fellers will be climbin' on!" he retorted, and held the throttle wide. As we flashed past I turned and saw one man miss the steps to our first car and go under the wheels; as I turned back, another had leaped for the cab and was grappling with Martin. I made to raise my carbine but the fireman was quicker yet; there was no room in the cab to swing so he thrust with his poker as if it were an epee. The tip took the raider in the head and toppled him from the cab; MacLeod held tight to Martin's coat and prevented him from going over, also.

We had only a second to catch our breath before MacLeod swore a fearful oath and sprang at the control levers. He was too late; in our moment of inattention we had closed the gap on the fleeing raiders and the nose of the Governor Barlow struck their flatcar at a difference of some twenty miles per hour. The bags of grain they had piled at the rear in a rude breastwork went tumbling and the riflemen behind them also. As MacLeod reduced our speed we fell behind again, but I could see we must give those riflemen no chance to recover. Our locomotive was made of stout iron, but a bullet could still penetrate its shell at close range, or a ricochet might injure or kill one of us in the cab. Another mile clicked by as we built up speed and came surging forward again. This time I did hear a bullet spang off the windscreen by my elbow, but again we hit them solidly. Bags and men went sliding off the sides, or were tumbled across the bed of the flatcar. Twice was enough; without regard for the men remaining on the flatbed car, the raiders uncoupled it from their tender and steamed away.

We were forced to stop. By slamming our engine into a car we had been courting derailment, either of that car or of our own locomotive. The Governor Barlow had a nose coupling, but unless it was firmly attached to the coupling of the other car, we could not dare push it ahead of us for any distance. The flatcar lost speed rapidly on the next upgrade and we came to rest just before the crest of the hill, held in place by our train. Immediately, we swarmed off.

Covered by our carbines, Dobbins went forward to take the surrender of the three men still aboard the flatcar; all were disoriented and only one still had a gun. Then we had to face the question of what to do about the inconvenient car. I toyed with the idea of rebuilding the breastwork and using it for our own cover, but then rejected the idea; there was no reason to think it would work better for us than for the enemy. MacLeod rummaged in a built-on chest on the flatcar and found a length of stout hawser, which he ran from the far side of the flatcar around a stout pine tree and firmly tied to the front of our engine. With the train slowly reversing, the flatcar lifted up, and with all of us including our prisoners pushing at the underside it went completely over, clearing the track.

Taking new heart and new energy from this success, we stoked the firebox to the limit and the Governor Barlow roared ahead.

The old work train was not capable of the speed our fast, new express locomotive could reach; even towing four cars we could attain more than half again their best speed. And so it was not so very long before we once again saw the dark bulk of the fleeing tender ahead, and saw the tiny winking lights that meant gunfire was coming our way. We came roaring up behind them, taking advantage of any little curve in the track to return fire, to no effect that I could see. We continued in this way for a few minutes, rapidly closing the gap, before MacLeod looked over at me mouthed a question. I motioned 'On!' and he shook his head, so I seized the cutoff and wrenched it wide-open. Rather than argue, MacLeod grabbed a handhold, swinging almost off his feet as we slammed into the tender. While I was trying not to fall from the cab, the engineer was busy whistling steam and reducing our speed, to such good effect that the raiders actually drew ahead, rattling over a bridge and around a curve out of sight. But not out of earshot: what we heard then sent both of us for throttle and brake. From around that curve came the rolling boom of a collision.

The Huntsville freight had been towing a load of coal and pig iron, making slow going of a long gradual incline. Both locomotives were destroyed on the impact; the crew of the freight survived save for the fireman, and the handful of raiders who lived were made prisoner or had fled into the woods by the time we arrived.

A fanciful engraving of the accident, from an Atlanta newspaper.

There only remained the tasks of clearing the wreckage and reopening the road. It delayed the movement of Hood's corps by a single day, yet it was a delay fraught with consequences, for in the interim Sherman opened an offensive of his own.

There were three major railroad lines radiating from Atlanta. The Knoxville-Chattanooga road was in use by Sherman's army. The second ran west through Huntsville and branched to Memphis and Nashville. The third ran eastward to Augusta, Charleston and eventually to Richmond. In Beauregard's opinion, Sherman would strike against the westward road if it were his intention to isolate Atlanta from the troops and supplies in the west. A blow to the east could hint at a greater design of severing Atlanta and the western states from the Atlantic states. For weeks, scouts had been reporting a vast buildup on the western side of the entrenchments that stretched half-way around Atlanta, but Beauregard remained unconvinced. The elections were coming in November, and Sherman would have time and force for only one attack; Beauregard believed Sherman would go for a knockout, and he was right.

Despite all the preparations we could make, Sherman's attack was sprung with a power that said the North had at long last learned how to fight. Led by brigades with Spencer repeating carbines, and followed up by McPherson's veteran corps, the Federals came on out of a foggy dawn in seemingly endless waves of blue. Through the morning our right was thrown back, and time after time it seemed as if threatening disaster must surely overwhelm us. I myself was almost caught; in the twilight hours our men had retreated all the way back to the Augusta railroad line, forming a last defensive line not fifty feet in advance of the tracks. Despite the danger, train crews volunteered to take fresh troops and ammunition into the heart of that furnace, and brought wounded back from it. My own locomotive tender took a three-inch shell through the water tank. I remember the cheers as General Patrick Cleburn rode up, dispirited and defeated men galvanized by his presence. And I remember him screaming, 'Don't cheer me, g**-d*** you, pick up your guns and fight!' He summoned them to one last effort, and by a miracle the Union tide was held, and that was the end of the first day.

During the night I rode in to General Beauregard's headquarters for his council of war. "This army is defeated here, but we can retreat to a stronger position and fight again," said one general. "Losing Atlanta is bad, but losing this army is disaster," said another.

Pat Cleburn said, "This army can't retreat. We couldn't get out before morning, anyway. Face it, gentlemen: we win here. One step back is the death of us."

Beauregard asked me. "I have no trains, no locomotives to haul the sick, the supplies or the manufacturing equipment of the city. Every engine I have is coming east with Hood's men. The first cars will reach Atlanta at midnight."

Beauregard nodded, slowly, and looked around the room at his officers. "Roll the trains through Atlanta and unload them at Davis Station. Make as little noise, and as much haste, as you can."

"I can unload the trains and then have troops make noise as though they are boarding. We can send the empty cars on toward Augusta - the enemy may think you are pulling out."

"I don't expect Sherman to fall for it," Beauregard said. "But I will accept any advantage, no matter how unlikely. I will establish my headquarters there, and will confer with General Hood as he arrives."

With that, the meeting broke up, and Beauregard and I departed for Davis Station.

It is not difficult to unload thousands of men in the dark at a tiny rural train platform; it is impossible. Nevertheless between midnight and dawn we managed to unload endless trains off the south side of the cars. An enthusiastic battalion of men cheered and clattered as they pretended to board the now-empty cars; sometimes a band would play as the train pulled out. In the wee hours before dawn, we drank endless cups of bad coffee as Beauregard and Hood sorted the troops out and moved them into approximations of where they should go.

It became painfully apparent that dawn would not find us ready to attack, and Beauregard was almost frantic at the delay. "If they attack us here, first..." he would say, but could not bring himself to complete the sentence. Hood offered to make a spoiling attack with a division, but Beauregard demurred. "We must strike with everything we have," he said.

At dawn the roar of cannon and rifle-fire rose up, not from in front of our position as we had feared, but rather to the west - beyond Atlanta! Sherman had opted to strike at the other rail-line! Beauregard did not believe Sherman had the strength to launch attacks on both sides of the city, and thought this attack might be a feint with a double purpose. Firstly, it might induce us to move our reserves there, opening the east to a new assault; secondly, an attack would reveal if Hood's troops were there. Fortunately for us, the left wing was commanded by General 'Prince John' Magruder, a man whose talent for theatrics had never been more on display. From black-painted, wooden false cannon to meaningless but impressive signal-flags and bugle-calls, he kept up the pretense of great activity, culminating with a chorus of 'Yellow Rose of Texas' and three lusty cheers for General Hood!

At any event, by half-past nine of the clock the attack on our left was stalled and most of Hood's men were ready to go, though we continued to unload brigades throughout the battle. Many units came off the cars with guns already loaded and marched away without packs or supplies of any kind, so great was the urgency.

I was not present to hear General Hood's short speech to his troops, though I did hear the roar as they went forward and saw his body as they brought him in. At the head of his column, he was felled almost instantly they say, and if anything was needed to rouse his troops still farther, his sacrifice was that thing. Through a fortunate positioning, Hood's attack struck a brigade of Germans from St Louis who promptly collapsed, and the screaming tide of gray-clad rebels crumpled Sherman's left wing and drove it all the way back to its starting trenches of the day before.

With Confederate cavalry rampant in his rear and his tenuous supply line stretched to its limit, Sherman was unable to sustain his advance. Supported by additional troops, Beauregard carefully flanked the Union troops out of one position after another, hemming them at last in an impregnable position in Chattanooga.

In November, Abraham Lincoln failed of re-election; the war-weary voters of the Union turned out not only his administration but a great many Republican Congressmen and Governors also. President-elect McClellan might not approve of the Democratic party platform's call for peace, but the sense of the people as expressed at the ballot-box could not be denied and McClellan had sense enough to bow. But before Lincoln or McClellan could make an opinion heard, Confederate President Rhett released a carefully prepared and timed speech. He called for an end to the War, called upon Britain and France to exert their influence, and called for an immediate armistice. All but the most fiercely-partisan Republican newspapers picked up his speech, and a storm of approval broke over the nation - now, the two nations.

At long last, there was peace. I looked forward to repairing and rebuilding my life's work, to restoring the Great Southern to its pre-eminent position among the great railways of the world. Most of all I looked forward to the solace of my wife, and to the restoration of her health and happiness.

Alas, it was not to be.

- March - 4 troops

- August - 8 troops

- December - 11 troops

Steel - 11 units, weapons - 4.9 units, ammo - 4.1 units, revenue - $12.9 million, profits - $3.8 million

Historical: Of course, in our history General Hood wasted his army attacking Sherman around Atlanta. Sherman took Atlanta, marched at will through Georgia and the Carolinas, and Lincoln won re-election on a tide of good news from the battle-front.

Copyright © 2006 - E. Porter Hopson - All Rights Reserved.